Section, township, and range are the numerically quantified units into which surveyors mapped, labeled, and apportioned the western two thirds of the United States during the 18th and 19th centuries. The section-township-range system remains in use now. If you know a real estate agent, you can quiz her or him about the use of the system in the present.

Of course, far before the establishment of the United States, European kings and colonists, soldiers and surveyors had begun divvying up the land which had previously known only flora, fauna, and the indigenous Americans whose conceptions of “land ownership” are better expressed in terms of habitual, if not continuous, use and enjoyment, accompanied by a reverential familiarity with the features and cycles of land, water, and sky.

This post is a much-delayed entry in a series aiming to explain the size units and

history of agricultural land, especially the land I help to manage in Kansas.

You may want to look back at my earlier entry on the development of the acre as such a unit.

In subsequent posts I’ll discuss the more than century-long development of agriculture from homestead-sized parcels to the larger footprint of a modern farm.

Over the last several hundred years, surveyors have created a throughline from the colonial seaboard to the diverse ranges of Kansas and Colorado, the areas where I spend most of my time and energy these days. As a testament to the early and lasting importance of surveying, one may well consider the earliest days of the colonies of Maryland and Pennsylvania. The former had been granted land in 1632 under a charter by Charles I, while the latter was chartered by Charles II. Because of royal error in drafting the specifics of the second charter, the two colonies disputed the position of their shared border from day one of Pennsylvania’s establishment in the 1680s. The dispute simmered for decades until astronomer Charles Mason and surveyor Jeremiah Dixon in the late 1760s came to the colonies and solved that dispute with their eponymous Mason-Dixon line. This line, just below the 40th parallel of latitude and southeast therefrom through the DelMarVa peninsula, clarified the border between Delaware and Pennsylvania to the north and Maryland and Virginia to the south. As Mark Knopfler in his song, “Sailing to Philadelphia,” has Dixon say, “It was my fate from birth / to make my mark upon the earth.”

Mason’s and Dixon’s line was preceded by calculations of latitude and longitude, and included the system of designating acres, furlongs, and chains which I have previously discussed (see link above). In places, stone markers were erected as physical points upon their line. Their work ended that dispute, but nearly one hundred years later, the clarity of Dixon’s “mark upon the earth” was suffused with the blood and rancor of the Civil War.

A second testament to the prominence of surveying in the nation’s geographical and political development may be found in the careers of America’s first and third presidents. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, contemporaries of Mason and Dixon, were surveyors in the employ of the colony of Virginia and for their British kings. Washington’s service in the French and Indian War opened his eyes to the possibilities of expansion that resulted in the apportioning of the Northwest and Southwest territories from Virginia’s land. Washington also presided over the accession of the states of Kentucky and Tennessee by the end of his second presidential term. Thereafter, Jefferson’s monumental acquisition of land the Louisiana purchase brought most of the range that we now call Kansas and Colorado (and so much else!) into the American picture. As British, French, Spanish, and Mexican governments sold, lost, or ceded their territories, and as indigenous Americans died or were killed and displaced, soldiers and surveyors were almost constantly at work and moving west.

By the time of the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, nearly 50 years after the Louisiana Purchase, the open lands of the great plains underwent measurement and partition in units of scale far greater than the acre. Enter section, township, and range. (Have no fear, though, the acre persists to this day as a measurement in the U.S. and U.K. but is impractical for identifying parcels on the scale of the survey of areas as great as required for the several hundred thousand square miles set to be apportioned in 1854.)

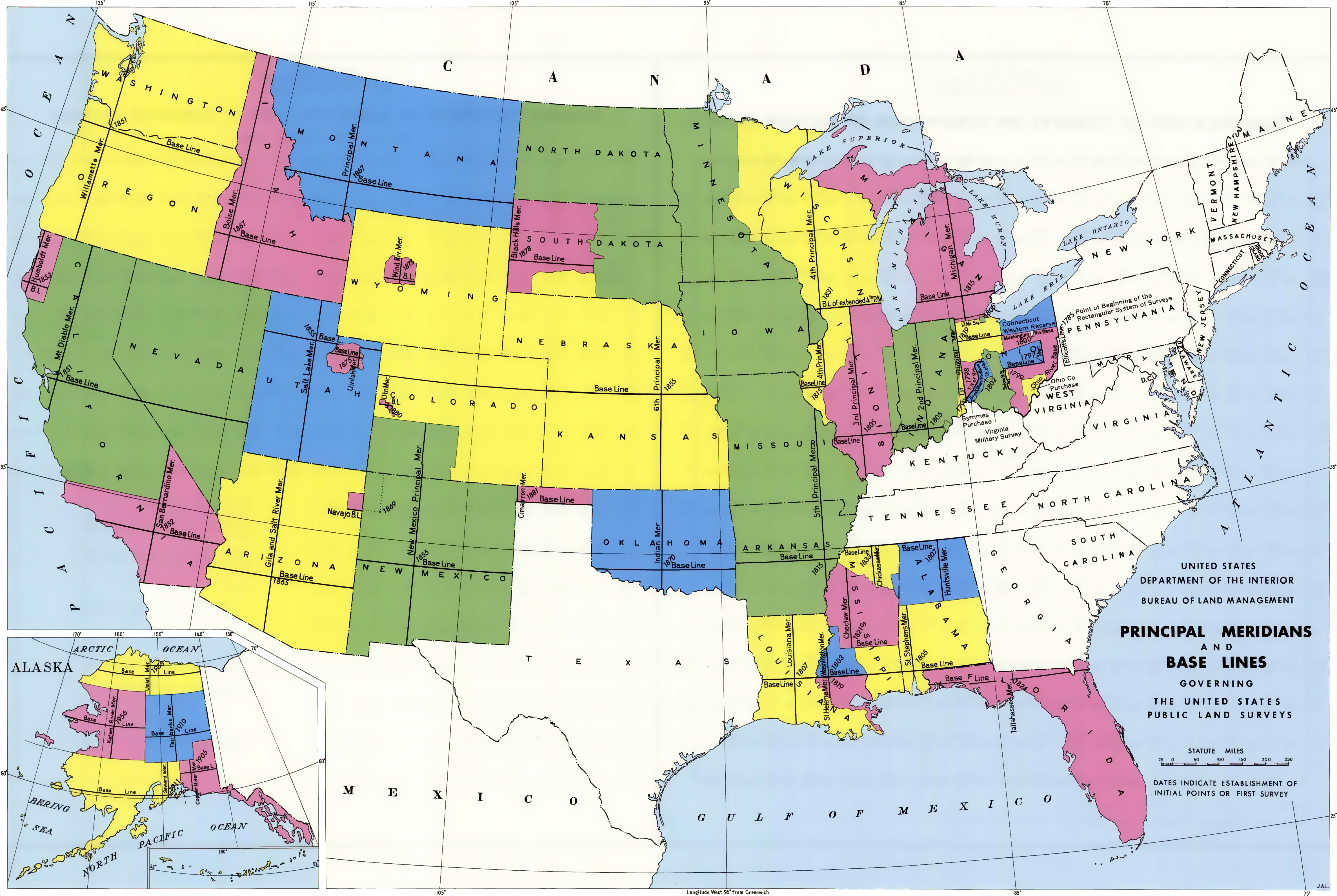

The scale of the task faced by surveyors in the 19th century was vast, as the image above makes clear. In the system adopted to cope with this vastness, surveyors always began from the point of intersection of two notional lines, one of latitude and one of longitude. The lines were regularly chosen so as to mark some inner point of the territory to be apportioned, rather than having some edge mark the start of the parcels. You’ll notice these intersections in most of the territories displayed above.

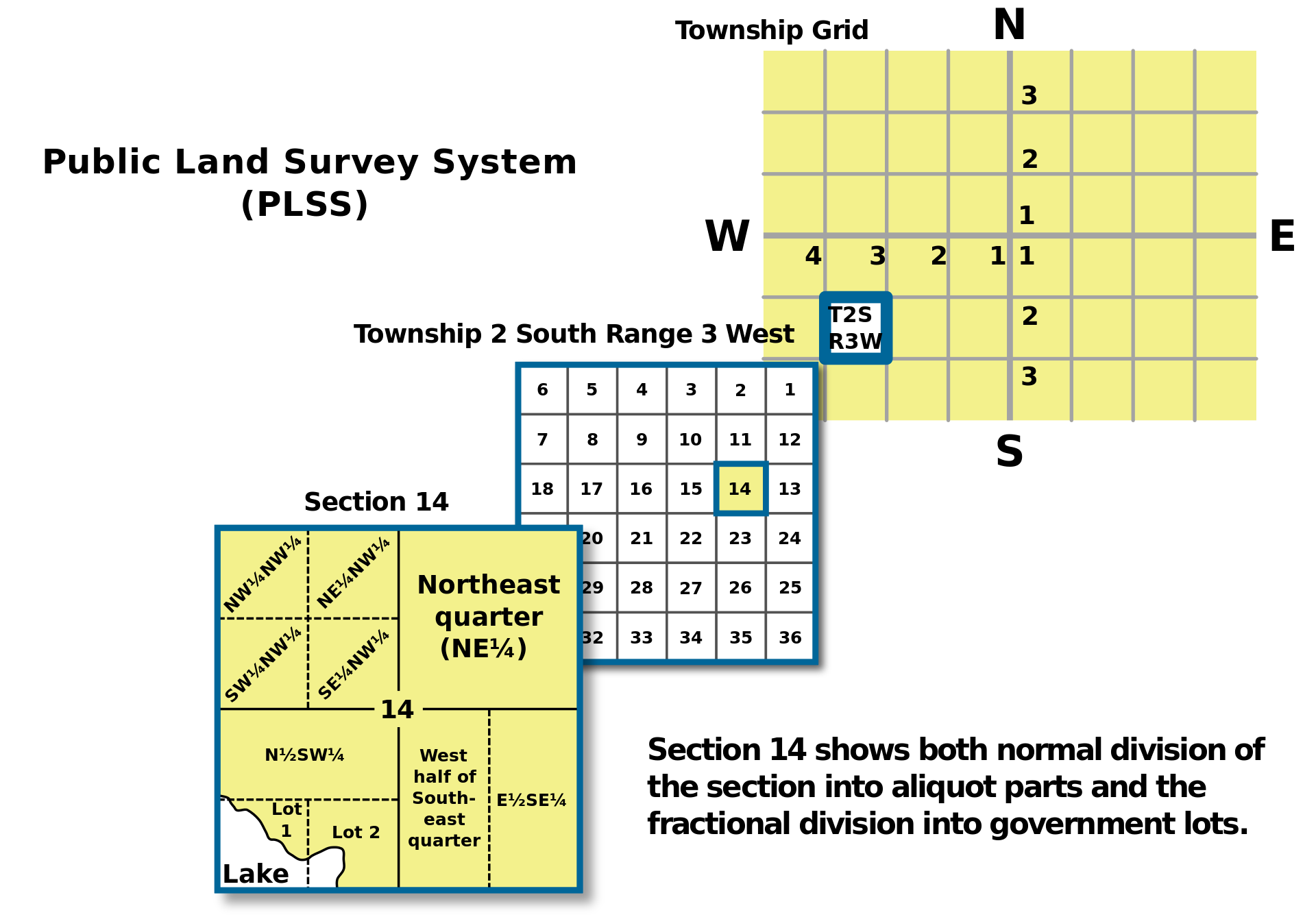

Once this the lines and their intersection point were set, surveyors reckoned and numerically indicated position:

- north or south of the set parallel of latitude; that parallel was designated as the base line (sometimes spelled as one word);

and - east or west of the set meridian of longitude; that meridian was designated as the principal meridian.

In the four directions from the intersection of the base line and the principal meridian, surveyors divided the landscape using numbered units the:

- township, (a 6-mile-by-6-mile square) of 36 square miles (23,040 acres); each township was numbered in a way that located it in position north or south relative to the base line;

- the range, as an additional numerical designator attached to the township, denoted its relative position east or west relative of the principal meridian; and, further, each

- township was divided into 36 numbered pieces, each of these being a one-square-mile unit; and each numbered

- section, whose one-mile dimensions per side resulted in a unit made up of 640 acres; and the section was routinely divided into four parts, each known as a

- quarter or quarter section, which is (phew!) what it sounds like, an area ½ mile wide and ½ mile long, amounting to one fourth of a square mile comprising 160 acres; and

- while the quarter might be subdivided into further sub-units such as the quarter of a quarter, additional subdivision hardly matters to us. Parcelling into blocks and lots is possible, but those are a level of detail that is usually neither necessary nor helpful when discussing rural land.

If you’re feeling lost in these geospatial and mathematical abstractions, you’re probably not alone. Suffice it to say that visual tools will illustrate the method in the madness. And it’s a method with which we all must live, for the results of the survey mandated by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, initially published in 1855, shaped the future of both the region where I live and the farm ground that I help to manage. If you live in the United States, chances are good that you live on land that was shaped and labeled similarly under what is now called the Public Lands Survey System (PLSS).

Survey results helped shape and label time and history, too. Per the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the border between the two territories was set at the 40th parallel of latitude, coincidentally reproducing what was to have been the original northern border of Maryland. Thus, nearly one hundred years after Mason and Dixon, the 40th parallel became the “base line” for the surveyor’s partition of the territories of Nebraska and Kansas. By the time Kansas became a state on January 29, 1861, the Mason Dixon line marked a border not between two colonies or states, but between two de facto nations: six of the eleven the Confederate states had already seceded, splitting away along one of the great American fault lines, slavery.

As an aide to visualizing the survey method, examine this screen capture from the Section-Township-Range Finder tool operated by the Kansas Department of Health and Environment. I used it to spotlight the intersection of the Kansas-Nebraska state line (the base line, near the top of the image). Also prominent is the principal meridian (running vertically in the center of the image). I’ll explain my annotations (in the white rectangles) below.

Like the base line (just below the white rectangle identifying Nebraska to the north) and the principal meridian, the section lines are shown in the thick dashed green lines. The finer green lines show divisions into quarter sections, public rights-of-way, or, in one case, the edges of a small parcel which may be public land. (Forgive me for not knowing for sure. I’ve never visited the area).

Just east and south of the intersection of the base line and the principal meridian lies the town of Mahaska, Kansas. Do you see it there, stretching north and south along the eastern edges of sections 6 and 7? Both of those sections are in Township 1S 1E, which signals that it is the first township situated south of the base line (1S)and also the first township east of the principal meridian (1E). Directly to the left of Mahaska and across the principal meridian, you see sections 1 and 12. They’re west of the principal meridian, thus not in the same township as Mahaska. Rather, they are part of Township 1S 1W, which you’ll understand means that it is the first township south of the base line (1S), but the first on the west side of the principal meridian (1W).

Here’s the image again. Note now that each section is subdivided into quarters. In shorthand notation I’ve labeled the southwestern quarter of section 12 with the designation SW 12 1S 1W. The descriptor’s initial two elements (in green) designate the location of the smaller parcels (quarter and section), while the two elements in black together indicate the position of the township. You could also consider the monstrous designation of the fractional parcel positioned near the bottom right corner of the image. Notice that its green lines indicate a subdivision of the southeast quarter of section 8 with the messy designation SE SE 8 1S 1E. In this instance the initial three elements (in red) together designate the location in terms of a fraction, a quarter of a quarter of a section, i.e. the southeast quarter of the southeast quarter of section 8. Again (and always!) the last two elements (in blue) together indicate the position of the township, which like the sections in which Mahaska lies, is in the first township south of the base line (1S) and the first east of the principal meridian (1E).

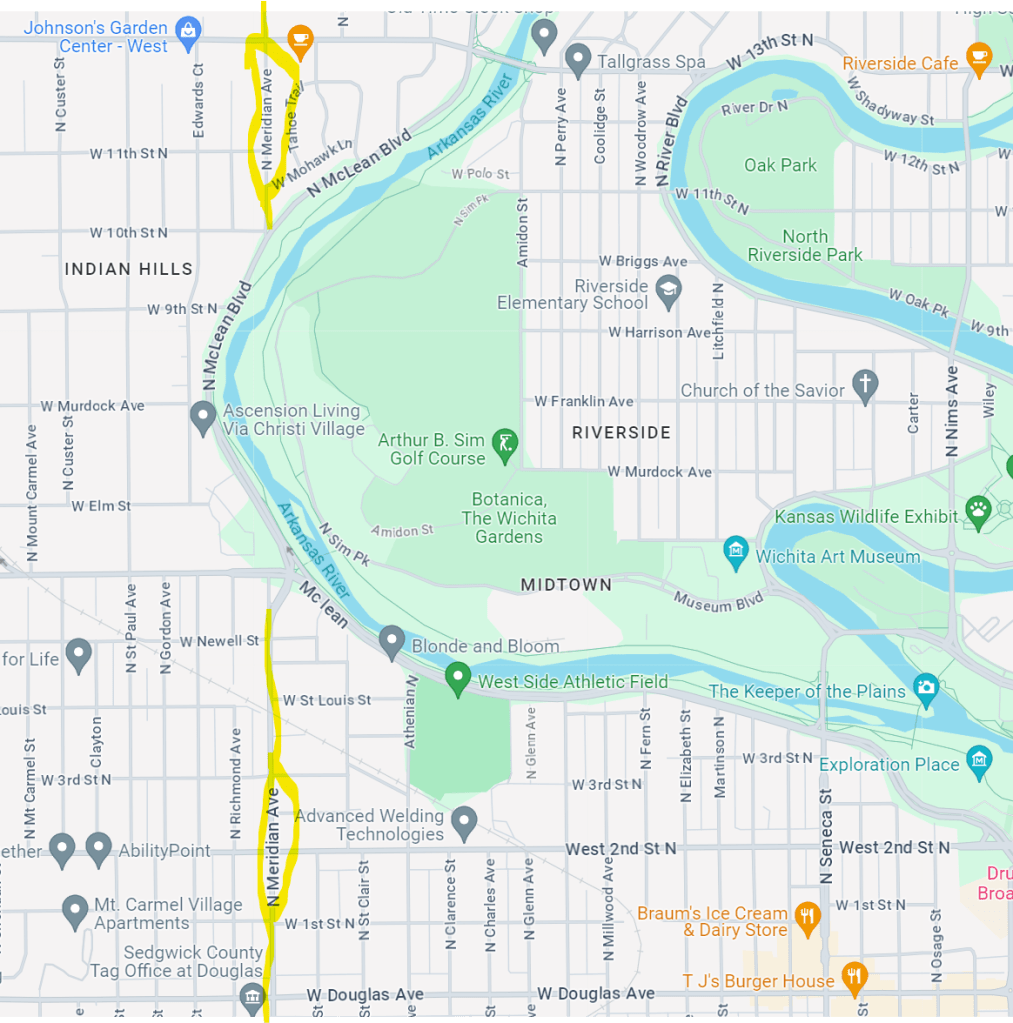

Within this system, every piece of ground in the former Kansas-Nebraska territories has its unique identifier referring to the base line and principal meridian. 200+ miles south of Mahaska and right on top of the 37th parallel (which defines the border with Oklahoma), you will find land designated as 18 35S 1E for section 18 in the township that is the 35th south of the base line and first east of the principal meridian. These terms also appear as street names in some cities. As a segment of it passes through Wichita, the principal meridian is memorialized in the name of Meridian Avenue.

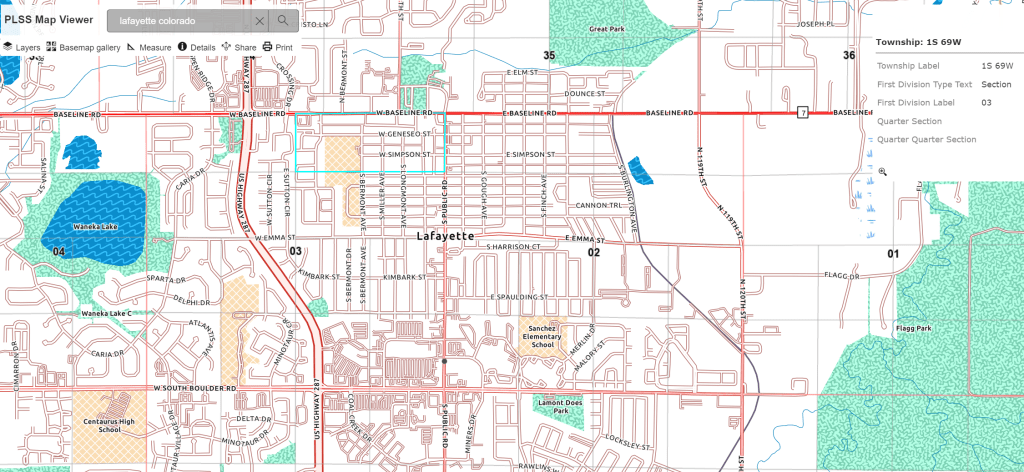

And the base line stretches all the way west into and Colorado and through it to the border with Utah. In Boulder County and its municipalities, the base line is memorialized in the name of Baseline Road. In Lafayette, the city at the southeast corner of Boulder County, Baseline is at the heart of town. I elevate my heart’s BPM at The Baseline Gym (102 W Baseline). Just a bit west and on the north side of Baseline is Lafayette’s original cemetery. (It’ll be a short haul if I exert my heart too far past its baseline rhythm at the gym!). Here’s a screenshot of the best parts of Lafayette. The gym is at the very northeast corner of NE 3 1S 69W, the northeast quarter of section 3 in the first township south of the base line, which is also the 69th township range west of the principal meridian, more than 414 (6 x 69) miles west of Mahaska, KS.

Further west is Lafayette’s public library, the city’s waterworks, etc, passing out of city limits and heading on to Boulder. In the city of Boulder, Baseline marks the southern edge of the CU Boulder campus, and is just yards from the National Institute of Standards and Technology. A marker commemorating the survey of the 40th parallel here (in 1859) can be seen on the south side of Baseline.

Pro tip: click on any of the images remove the obscuring caption and to see the image full-sized. Image credit to the author, March, 2024.

Another historic landmark, Colorado’s historic Chautauqua is at Baseline’s west end, just before the road twists its way into the foothills, changing name and contour as it climbs Flagstaff Mountain. Chautauqua Park and the rising ground below Boulder’s Flatirons are visible at the right of this image. (As you can see, this has become the range where Pierre and his motorcycle play!)

At this point you may be wondering when I will return to writing about farming. Look for my next post to move from surveying to discuss the agricultural and economic dimensions of the Public Land Survey System, starting from how it created homesteads in Kansas (and elsewhere) from 1862 until the present. I’ll discuss what a quarter (quarter section) meant (in terms of cost and livelihood) to a pioneer, and what it means within the economic lives of contemporary farming families in southwestern Kansas. We’ll start during the American Civil War, and end in 21st-century Stanton County, which aptly is named in honor of Edwin M. Stanton, President Lincoln’s Secretary of War.

If you’d like to keep up with my writings about agriculture and other adventures, please subscribe to my blog using the field below. You’ll get a single email announcing new posts. I aim to post once per week.

Additionally, please use the Leave a Comment area further below to pose any questions you might have about what you have read or are curious to know. (There are so many dimensions of the Public Land Survey System that I did not discuss, such as the boustrophedon numbering of sections within a township, or how the surveyors dealt with the curvature of the earth!)

I will certainly respond and possibly give an extended answer in a future post.