It doesn’t matter whether you are in Kansas anymore. Nor whether your name is Dorothy. If you are buying, renting, or selling land (especially land for agricultural use) in the United States, you’ll likely encounter the acre as a fundamental unit of measurement. It’s true that there is no place like home, but there is no home without some multiple or fraction of an acre keeping it from falling into the abyss.

Or falling onto a witch. (You may wonder why the witch didn’t simply duck as the wooden house, spiraled down upon her, but you’d need to consult with King Arthur or Sir Bedivere as to why the witch elected not to duck.

Physical Dimensions, part I

If you have no patience for my allusions to film, nor for the linguistic and historical descriptions of the acre which will follow, here is the contemporary “Just the facts, ma’am” definition of an acre: an acre is an area of 43,560 square feet or 4,840 square yards. (That smells suspiciously like a huge algebra problem waiting to happen.) An acre is also 1/640th of a square mile. (Now the acre seems like a miniscule unit with which to survey tracts of land, whether such tracts are truly huge or merely modest).

In Europe proper and elsewhere, you’ll encounter the hectare (10,000 square meters) as the standard for measuring land area, but throughout most of English history and here in the U.S., the acre reigns supreme. It behooves us to understand what it is, and in units that are not the foot, yard, or mile. Such merely numerical descriptions as those above neither warm the cockles of my heart nor flash a clear image of the acre in my mind’s eye. Comparisons to a regulation playing surface for a sport are possible, but (for me, anyway) it is always hard to mentally separate the playing surface from its encompassing sidelines, benches, and seating for spectators. I offer comparisons to various at the end of this article, but I find it much more instructive to write and share why an acre is an acre in the first place. Perhaps in reading what I offer, you’ll develop your own grasp of both the origins and the scope of this term of land measurement. Lest your feet become tired and tiresome ache-ers, you might better exchange your ruby slippers for sturdier footwear as we walk together through the history of the acre as a word, the ways that it can be quantified in more standard units of measurement, and suggestions for how you can visualize an acre in your world.

In future posts, I’ll write about the use of the acre in the surveying and parceling of land

in the westward expansion of the United States, and the current market value

of some of the acres that I help to manage in southwestern Kansas.

Thereafter, I’ll discuss the agricultural and economic productivity of those acres

(in bushels and dollars) before returning to discuss what all that means

for the lease-holding farmers with whom I collaborate.

Linguistic dimensions

Acre has its linguistic origins at the root level of the family tree of Indo-European languages. Acre springs from the root *agro- which denoted open land, and thus land suitable for tillage. In the Germanic branch of the family, (of which Old English and modern English are both members) the guttural consonant –g– phonetically shifted toward the palate, resulting in a sound closer to the initial consonants of the English words cord or king. Thus, English acre sounds very similar to its German and Dutch cousins acker and akker, respectively. In Latin we find the original guttural preserved in the word ager (plural agrī), and the -g- sound persists in the many English words directly borrowed or built from this Latin root, such as agriculture, agrarian, agronomy, etc. (For more on the origin and history of English acre, consult this Etymonline article).

Historical dimensions

Acre, soon took on a uniquely specific significance in mediaeval English culture and, eventually, law, as it came to signify the amount of land that a ploughman and his yoked pair of oxen could till in a single day. As an approximate measure of land area, this loose quantification of an acre is, we may suppose, a not-irrational way of allotting grants of land in varying numbers of acres to nobles at least partly based upon the number of retainers that said lords have to turn such land into productive (and taxable!) use. But it is not fully rational, either. In practice, how much land a ploughman and team can work in a day is dependent upon many variables ranging from soil type to weather to hardiness of the draft animals to durability of the equipment to the skill and energy of the ploughman.

Speaking thereof, what would a 15th-century English ploughman tell us about the acre and his toil upon it? As an exercise in imagination, let’s picture such a ploughman fresh out of the alewife’s shop where he has enjoyed a pint with his lunch and is headed back to his plough and oxen.

A caution: be prepared for some lack of clarity when discussing units of measure. As an example, if you are an American reader, you think of a pint as 16 fluid ounces, while in the British Imperial System, our happy ploughman enjoys a pint of 20 fluid ounces!

Hey, where is our ploughman? He seems to be enjoying a second pint in the shade of that elm across the road. A man after my own heart! While he finishes it, put yourself behind the plough and imagine doing the most critical part of his job, which is keeping the ploughshare moving properly deep and straight in the ground while managing his oxen. What allows him to give the least energy to managing his oxen and the most to managing the blade at a proper depth and opening the ground efficiently so that his furrows aren’t too far apart (wasting good, fertile earth, etc.), nor too close (which will cause excess competition between the rows of growing crops)?

Keeping the oxen running as straight as possible from a field’s starting edge matters, as does maintaining equidistance from the other furrows that have been plowed. Another way to consider it is to ask what the action is most likely to lose evenly-spaced, straight, and properly deep furrows Even if one were driving a tractor or sitting above the plowshare rather than walking behind it, you’d find that re-establishing your line and sinking the plow’s blade after the turn at the end of the furrow are hard to execute. But one can’t avoid turning, for the cart of seed that the sower is dropping into the furrows and the water for the oxen (and perhaps a spare pint or two!) are waiting back at the end of the field from which the work begins. To confirm your inference that a day’s work plowing in a field will produce furrows fewer in number and greater in length, you look across the field to its starting edge and notice that he only plowed a few furrows before lunch. As you look down the field to its far end, though, the furrows blur into the horizon. The ploughman’s work so far that day has, in fact, produced a long, skinny rectangle.

As you are idling beside the oxen, the ploughman, second pint quaffed, approaches to resume work. You quietly wonder whether he’ll be able to keep the furrow straight after his 40 ounces of ale, but choose to ask him instead about his work as he resumes tilling. He returns your greeting and agrees to your request for information, instructing you to walk along beside him (on the unplowed ground, of course!). He tells you that he is Clay Turner, son, grandson, and great grandson of ploughmen, all retainers of the local noble family. He adds that he’s obligated to plow an acre of the field each day of sowing season. He confirms that the acre is always a very elongated rectangle and gestures, “Like that neatly trimmed hedgerow between those lanes leading to and from my lord’s manse. But tipped on its side, of course.” You note that he’s obviously not tipsy himself, as his furrow is straight and even. You ask him how far he and the oxen till the ground in a line before turning around. “Well,” he explains, “ since my great-grandfather’s time and even before, a good ploughman and his yoke always run a furrow long up the field, and a furrow long back down.” You think that hat’s what he said, anyway, but since he somewhat slurred the ‘-row’ of ‘furrow,’ you begin to think he had more than two pints with lunch. And then it hits you. No, not the ale on his breath, but the fact that he and his team plow a furlong. You remember that you’ve vaguely heard of a furlong as a distance in the context of horse races, and you reason that just as a work assignment that lasts a week has a weeklong duration, Mr. Turner’s rows are each a furlong (a furrow long) from start to finish.

But though you’ve heard of the furlong, you’re still not sure how long the furrow is. Indeed, a weeklong assignment might be for seven days (a calendrical week), or a mere five days (the conventional work week). When it comes to quantifying a furlong, you don’t need to rely on a slurring ploughman’s word. Let’s leave Mr. Turner to his work and turn to standard units of measurement to find precise answers. Etymonline or Britannica document that what was once just an approximate furrow length arising from the practicalities of plowing and sowing was converted into a standard unit of length during the reign of Elizabeth I, a standardization that included the lengthening of the old Roman mile (5,000 Roman feet) so that it was defined as 5,280 feet. The customary furlong was codified as 660 feet (220 yards), precisely one eighth of the new English mile.

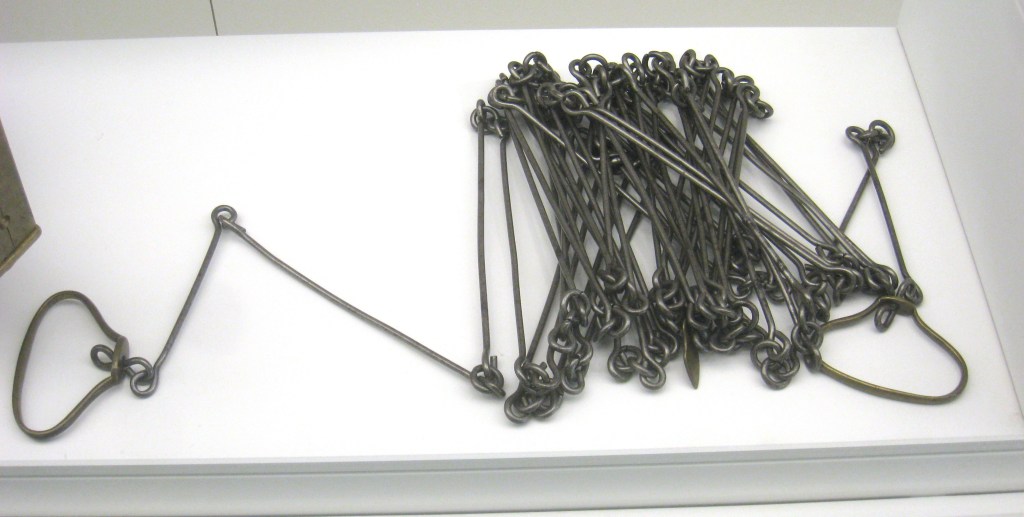

As we learned in our conversation with Mr. Turner, a second key element in the centuries-old conventions of oxen-powered planting is that in a day’s work, the length of the ploughed area (the furlong) would be about ten times greater than its width. In the early 17th century, that width was codified, too, as 66 feet (22 yards), exactly one tenth of a furlong. And soon this codified measurement was given a distinct name. Bearing in mind the physicality of measuring in those times (lacking GPS, lasers, radar, and the like), it’s easy to accept that this 66-foot distance was originally measured using a standardized length of wood known as a rod or pole (16.5 ft. or 5.5 yards). Four rods equals 66 ft. Soon, that multiple of the rod came to be measured using a metal chain, four times the length of that smaller unit.

Physical dimensions, part 2

Sparing the rod for the moment, let us focus on the chain. The surveyor’s chain was designed in 1620 by an English mathematician named Edmund Gunter and greatly simplified the theory and practice of surveying. Larger and more practical than the rod, the chain’s length (66 feet) became the fundamental standard unit for measuring land. The chain itself served as the mechanical tool of surveyors, as it is a true-to-its-name chain made up of one hundred (100) links, so that fractional measurements were possible. It matters somewhat that each link was 7.92 inches long. It matters much more that there were one hundred (100) of them in a chain and a thousand (1000) of them in a furlong, since a furlong is ten (10) chains. In other words, one begins to have a decimal-based system with which to measure not only length, but also with which to calculate surface area using multiplication. Additionally, a chain, though heavy, is both physically and mathematically much more wieldy and efficient than its predecessor, the rod.

Fractional (or decimal) ratios to a mile of a chain (1/80th) & of a furlong (1/8th) are also comprehensible. The table below is excessively detailed, if you let your eyes go to the bolded cells, you’ll perhaps see that the math attached to rods, chains, and furlongs is quite doable.

| Unit Equivalents | Feet | Yards | Rods | Chains | Furlongs | Mile |

| Yard | 3 | 1 | 2/11ths | 1/22nd | 1/220th | 1/1760th |

| Rod | 16.5 | 5.5 | 1 | 1/4th | 1/40th | 1/320th |

| Chain | 66 | 22 | 4 | 1 | 1/10th | 1/80th |

| Furlong | 660 | 220 | 40 | 10 | 1 | 1/8th |

| Mile | 5280 | 1760 | 320 | 80 | 8 | 1 |

Moving from lineal distance to area, we can define the area of an acre in its old-school definition: an area 1 chain in width by one furlong (10 chains) in length. In square units, this is 10 square chains. (Yay for round square numbers!) On another piece of ground, an acre could also be defined as a parcel 2 chains by 5 chains. If you want to visualize it as a true square, each side of it would measure approximately 208 feet (approximately 70 yards), or approximately 3.16 chains on all sides.

Physical dimensions, part 3

If comparison to easily-defined contemporary areas is helpful, here are some factoids about the area of athletic playing surfaces which you may consider:

- A regulation doubles tennis court is 312 square yards; omitting the run-offs surrounding the fair-play perimeter, 15.5 courts would fit in an acre.

- A regulation NBA basketball court is 4,700 sq. feet; 9.25 courts (in-bounds area only) would fit into an acre.

- A regulation NHL rink is approximately 16, 600 square feet (the rounded corners make the math less than straightforward); approximately 2.62 rinks would fit in an acre.

- An American football field, including end zones, is 57,600 square feet or 6,400 square yards; minus the end zones, it is 48,000 square feet and just over 5,333 square yards; either way, it’s over an acre; however, if you picture the area from the 20 yard line to the end of the opposite end zone, you’re looking at just a shade under an acre.

- Major League Baseball and FIFA soccer do not mandate diamonds or pitches of a single standardized area, but in Colorado …

- the area within the foul lines and the outfield walls at Coors Field is, by my calculation, approximately 2. 5 acres.

- the playing area for the Colorado Rapids at Dick’s Sporting Goods Stadium is 9,000 square yards, just over 1.85 acres.

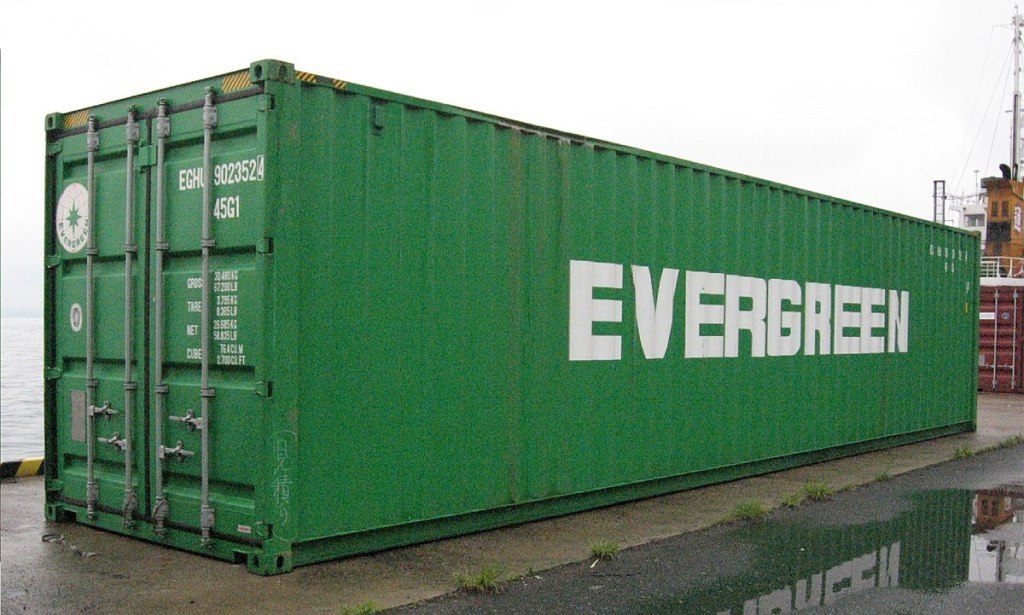

One final attempt to help you visualize an acre: we’ve all seen a standard 40-ft. shipping container on a train, the bed of a truck, or at a construction site. At 8 feet in width, 136 of them will fit side-by-side and end-to end in an acre.

Well, we have certainly strayed very far from where we began. But thankfully, that’s everything that you might want to know about the history and dimensions of the acre as a unit of land measurement. Yep, that’s all of it in a coconut shell. I hope that it was not too much to swallow.

I’ll head back to the farmland in Kansas for my next post. I can almost hear the clicking of my ruby slippers. Can you?

If you’d like to keep up with my writings about agriculture and other adventures, please subscribe to my blog using the field below. You’ll get a single email announcing new posts. I aim to post once per week.

Additionally, please use the Leave a Comment area further below to pose any questions you might have about what you’ve read or what are curious to know.

I will certainly respond and possibly give an extended answer in a future post.

One response to “Acres and Furlongs and Chains, Oh My!”

“You may wonder why the witch didn’t simply duck as the wooden house, spiraled down upon her, but you’d need to consult with King Arthur or Sir Bedivere as to why the witch elected not to duck.” I think that if the witch weighs the same as the house, the gravitational pull between the two precludes the witch’s attempts to dodge her fate and avoid becoming really most sincerely dead.

“a pint of 20 fluid ounces!“: They come in pints? I’m getting one!

“Clay Turner”: Ha. Clever. Here’s another mediaeval plowman, speaking about his obligation to finish his work before he can leave his field:

‘Quod Perkyn the Plowman,

“By seint Peter of Rome!

I have an half acre to erie

By the heighe weye;

Hadde I eryed this half acre,

And sowen it after,

I wolde wende with yow,

And the wey teche.”‘

_Piers the Ploughman_, ll. 3799-3807

(Said Perkin [Piers] the Plowman,

“By Saint Peter of Rome!

I have half an acre to plow

By the high way;

Had I plowed this half acre

And sowed it after,

I would travel with you,

And the way teach.”)

Thank you for the enjoyable history on the early evolution of land measurement and management. This was well done and I enjoyed the associations to other cultural connections.

LikeLike