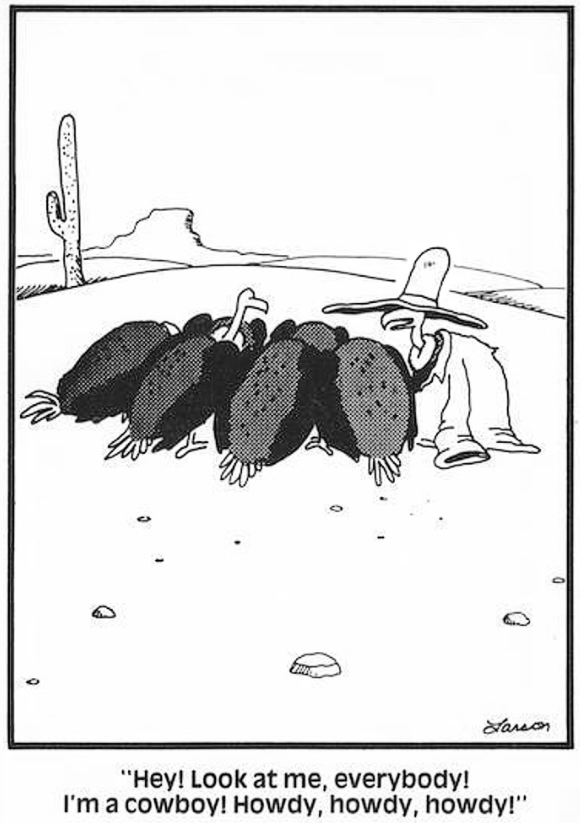

Managing farmland does not make me a farmer, not any more than wearing a ten-gallon hat would make me a cowboy. Nope, no matter how much a guy might want to be one, the hat doesn’t make the cowboy, as Gary Larson hilariously shows in The Far Side panel that’s always been a favorite of mine.

In addition to my lack of experience, equipment, and expertise, numerous additional factors mean that I do not farm the ground that I help to manage:

- the pieces of ground are widely dispersed, not a contiguous parcel: 90 miles separate the southernmost field from the northernmost field which are part of the ‘farm;’

- several generations back, the family relied on farmhands (employees) to help work the ground, but a rift in the family left a widow, the mother of two pre-teen girls, without employees;

- she, of necessity, shifted to a model of leasing the ground to farmers who became leaseholders (tenants); the widow faced numerous difficulties, many of which arose from the emnity of her deceased husband’s family; as a result, she often had difficulty in finding farmers or, to put it more accurately, she had to back them financially or otherwise as they overcame difficulties with debt, lack of equipment, or addiction; despite these hardships, she persevered and passed a successful model for farm management to her children.

The farm that I help to manage is very much a collaborative enterprise. As agent for the landowners, I have numerous responsibilities that bring me into business relationships with insurance providers, grain buyers and dealers, the USDA, the bank, etc. Outside of the family, however, my most important relationships are with the lease-holding farmers (and their families) whose expertise, equipment, and labor make the ground productive. Because the parcels of the farm are widely dispersed I have the privilege of collaborating with numerous leaseholders. Most of them I have known since I first started helping at wheat harvest decades ago. We’ve built closer and stronger connections now that I no longer teach and can give more time and attention to the enterprise and to the people who make it successful.

My experiences with the farmers have produced in me tremendous admiration for them, and I greatly enjoy their company. It is an joyous honor to attend the graduations and weddings of their children. And it is solemn duty to attend their loved ones’ funerals, balanced by the pleasure of being able to send books and other gifts to celebrate the arrival of diaper-clad members of the next generation. A third of our leaseholders represent the second generation of their families holding a lease with our farm, as now members of a third generation take on key roles in their operations. Most of the other leaseholders have members of their next generation working alongside them and ready to succeed as the heads of their own farming operations.

Because I have not sought license to describe any particular farmer (or farm family) in my blog, I will not profile any people in a way that identifies them. But let me generally say that they are pillars in their communities. One farmer is a council member in his city (population 132 in a county of 2,084 people) at the same time that he also sits on the board of the cooperative that provides crop insurance to the region. Another serves with his son as part of his county’s volunteer fire department, while yet another served for years on the school board. Spouses, as well as adult children and children-in-law, often teach or coach in the local schools, or help to staff the county hospital. Most farmers that I work with are also active in the leadership of their faith communities, and/or in 4H and other youth-centered organizations, and all the while keep their businesses functioning at a high level. They help their neighbors when there is an illness, weather disaster, or other crisis. Running their farms means that they must function as agronomists, financial officers, HR recruiters, crew managers, marketers, negotiators, mechanics, machinery operators, and, at harvest time, as choreographers of a four-combine, two-grain-cart, six-semi dance that can start at 10 a.m. and run ‘til 1 a.m. the next morning. And, if their operation includes cattle (boy howdy!), they also legitimately claim the hat and status of a cowboy.

In short, farmers and farming families work hard and do so for long hours in what can be extremely challenging conditions. The challenges are intellectual, emotional, physical, and economic. Farmers put a big investment in the earth and tend it there for up to nine months with no certainty that a hail storm won’t level the crop before it can be harvested and stored or sold. Suffice it to say that it is of tremendous importance that both the land-owning family (whom I represent) and the lease-holding farm family both prosper from the partnership that each forges with the other.

The key instrument to encourage such shared prosperity is the lease, the agreement which sets out each party’s obligations and how each party benefits from a leased parcel. In a future post I will discuss various types of lease structures that are in current use, the pros and cons of them, and describe in some detail the type that we rely on to ensure shared prosperity for landowner and leaseholder alike.

Up next, however, I’ll aim to give you a sense of the areas, volumes, and monetary values involved in farming, at least as we practice farming in southwestern Kansas: How big is a typical field? How much does it cost to plant, tend, and harvest a particular crop from that field? How much grain is in a bushel, and how many bushels will that field produce? What price will the farmer get for the grain from that field? These are not, perhaps, the sort of questions that set the reader’s heart a-racing, or indicate why farmers love their work, but they begin to get at an immensely important matter: what does it take for a farmer to gain a livelihood from the work that he or she loves?

If you’d like to keep up with my writings about agriculture and other adventures, please subscribe to my blog using the field below. You’ll get a single email announcing new posts. I aim to post once per week.

Additionally, please use the Leave a Comment area further below to pose any questions you might have about what you’ve read or what are curious to know.

I will certainly respond and possibly give an extended answer in a future post.

One response to “Howdy, Howdy, Howdy!”

I always enjoy the photographs you add to your posts. You have a good eye for your subjects.

Your description of the complex lives of farm families and the respect you have for them shines with a quiet passion. I hope you will continue to write about them in other posts.

And I am looking forward to your next posts about the scope of what it takes for farmers to make a living and to your discussions about various kinds of leases. I am learning a lot from your blog.

LikeLike