A long bit about a hike that filled time as rain put harvest on hold and as I waited to visit with my son as he faced an unsettling loss.

This segment is the fourth of a series featuring mountains both real and figurative,

climbs that are successful and not, and water that is varyingly life-giving, dirty, and toxic.

The series narrates experiences of me and of those around me in June and July of 2023.

There is discussion of suicide and other forms of untimely death in this series,

so please stop reading if these matters jeopardize your wellbeing.

If you are in a low spot of this kind, please reach out.

Reach out to me, to anyone you trust, or to the 988 help line.

Dirty water

Technology and the richness of digital resources allow one today to know so much about the trail which lies before one, and to anticipate many of the experiences that may unfold upon hiking it. This, for conservative and cautious me, makes getting up the trail an object of anticipation rather than fear. For all that access to said richness, many parts of the outing are still a mystery to be unraveled in the hiking: 1) What trail- and day-specific delights or torments (or both!) will I find along the way? 2) Will my work boots (more than twice as heavy as my hikers) make me stride at the pace of Young Frankenstein’s monster? 3) Will the people I meet on the trail be genial fellow adventurers or the sort of numbnuts who hike with a 7-iron and golf balls so that they can chip off the summit onto the world below? 4) Will the stream crossings and snow fields be passable, and will the “Considerable” rockfall potential take down this blockhead?

And then there is always the eternal internal question: how much physical stamina and strength of will do I bring to the mountain today? These unknowns encapsulate the literal challenges and rewards that so often make mountains a metaphor for the sorts of life situations which, at that very moment, lay my children (as discussed in the first post in this series). At this point the reader may be wondering what in the world I mean by ‘rewards’ in situations such as theirs. If you are shaking your head at my use of that term, I’d ask you to look within and consider: what precious person, experience, or change within yourself can you call yours because you got through travails that at one time felt insurmountable? Perhaps you gave life to a child after the terrible pangs of childbirth. Or you’ve built respect and connection with others that resulted after a period of suffering when you or they thought they were alone. Or you got a degree, a job, or a promotion through perseverance and merit, even if the latter was not recognized by others as you faced adversity.

Pardon me and my preachiness, especially when this is nominally a segment about neither real nor figurative mountains, but instead focused on dirty water ant the questions I enumerated above. I’ll get back to those now.

Delights, torments, and getting to the top

I made it to the top, with many delights and few torments, at a pace I can live with. Pictures will save us a thousand words or maybe more, though I can’t show you any images of the wind: it was at times considerable, but never reached the 30 mph gusts called for in the Red Flag Warning that was in effect. Thank goodness for that!

Wildflowers and a daytime moon brought delight, gracing the trail from bottom to well above treeline:

Umcompahgre’s ridge and summit offered splendid views of the rest of the San Juan range and of the snowfields and valleys among its peaks, though wildfire smoke obscured the Uncompahgre basin to the west:

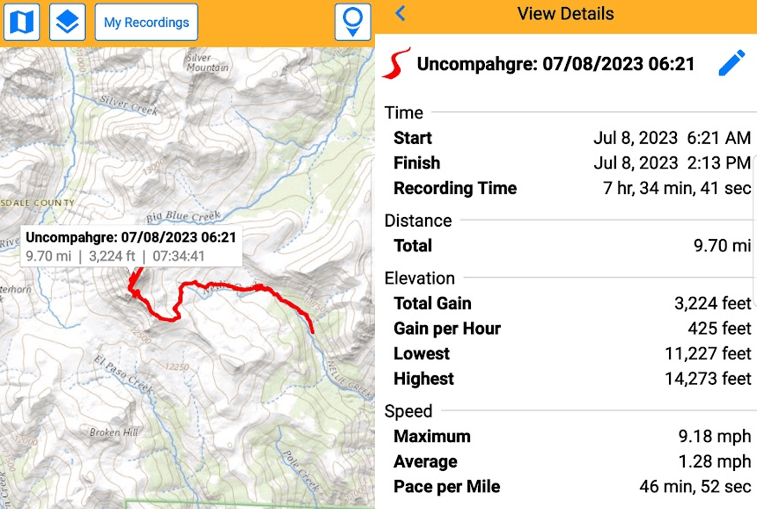

My average speed of 1.28 mph was, to my surprise, more than 10% faster than on any 14er attempt I recorded last year. Yay, I am less like a tortoise! And at nearly 10 miles, this was the longest 14er hike I had yet done:

Genial adventurers

The other hikers on the trail and at the summit were indeed genial. A pair of adventurous hiker-bro-dudes and I leap-frogged each other for the better part of two hours on the way up. They managed to converse at length with each other the whole climb, talking about other hikes and additional outdoor pursuits they enjoyed, their work experiences and travels, etc. (Sometimes, thankfully, distance from them or the wind muted the flow of their conversation.) I reached the crux of the route, a steep section requiring scrambling over loose rock that would make or break my climb, just ahead of them. While I stowed my trekking poles and a hiker descended from above, the dudes caught up with me. Here I was most happy to let the fearless younger folks go first, which they did eagerly and with quiet focus.

Elsewhere along the climb, I also had pleasant encounters with a few hiker duos (couples, a father and young son) and some solo folks. A small group that included a Ukrainian family taking refuge in Colorado reached the summit as I did. Amazingly, the 10-year old in the family was enjoying his 13th summit! Conditions at the top were delightful, and I enjoyed a prolonged stay to snack, take photos, and chat with those around me. The hiker-bro-dudes raised the topic of pronunciation and meaning of the peak’s name, neither of which they knew. One ventured that it was the name of the first person to find or climb it, à la Zebulon Pike and Pike’s Peak. I shared how I had heard it pronounced and my speculation that its name was from a Native American language. One said that he thought the peak’s name might be a Spanish word, since ‘un-‘ is a common Latin prefix that appears in Spanish. Despite knowing that this was true for un/uno/una, unidad, universidad, and such, I found his inference unlikely to hold water, but kept my doubts to myself, making a mental note to look it up later. Soon, my inner introvert (and the knowledge that half the hike remained) led me to separate from the others. I rested alone and prepared for the descent, as the downward path is often just as challenging for me as the way up.

Getting down without a sudden fall

Once I had doubled up my socks and unpacked my trekking poles, I started down alone. When I reached the crux, I remembered that the 14ers.com route description had listed two paths through it: “Walk toward the tower seen in photo 11 where you’ll have a couple of options: 1) Pass the tower (photo 12) before turning right to regain the ridge or 2) take a slightly steeper line just before the tower. Both options hold loose rock.” On the ascent, I’d taken the slightly steeper line as I’d followed the bro-dudes. I didn’t relish descending it. So I opted to try the other segment. It turned out to be slightly less steep, but the route-finding and the looseness of the rock (and gravel/ dirt!) certainly made it exciting. My footing gave way here and there, turning some intended steps into mini-slides. In my caution and slowness, the Ukrainian father and son came up behind me and passed to join the mother and friend who had already made it to firmer terrain through the steeper section. The other father-son duo passed me, too. All made it safely to that firmer terrain.

The downward trail had a few other iffy stretches for me: the snowfields had softened up as the day warmed and moving downhill sometimes gives gravity too much sway to my momentum. Firm, if icy, footings on the way up were slushy by late morning, causing steps sometimes to result in planting my leg up to the knee or in a slip that would help cool my hot hot hot butt in the snow for a bit. The increased rate of melting added water to areas of the trail that were crossed by rivulets which soon formed Nellie Creek. (Aside: Nellie parallels the trail for much of its length and indeed gives the trailhead its name. Nellie Creek’s waters continue into the Gunnison River and onward into the Colorado. The Uncompahgre River, too, flows into the Gunnison, though its headwaters arise to the west of Uncompahgre peak.)

My footsteps in these crossings stirred up dirt, which brings us back to the topic of dirty water. When I eventually got around to looking up the origin and meaning of Uncompahgre, I found that it originates in the Ute language. It means “dirty water” or “rocks that color water red,” and is a term that it is applied as a byword both to a band of the Ute people and to the areas which were their longtime homeland. I note now that the water I splashed in and the rocks upon which I trod, especially the sandstone and shale of the region, are also denoted by the Spanish name Colorado. It seems to me worth knowing and sharing that the peak, wilderness, river, and surrounding region is of a people more ancient than the Spanish- and English-speaking people who flooded into what is now called the United States, and the beautiful part of it which my family and I call home.

That’s enough about my hike to the Uncompahgre’s summit. Look for more regarding how my family dealt with their climbs in my next post.

If you enjoy what you’ve read, please post a comment. Likewise do so if you were troubled by it. Or use the contact button to send me a private message. And to have you subscribe to The PHurrowed Brow using the link below, well, I should like it of all things!

One response to “Water, Mountains, Climbs: IV”

As always, your eloquent photography is stunning. The shots of the scenery — the colourful palette of the flowers; the complex patterns of snow, ice, greenery, and rock on the peaks; the reminder of the fragility of the eco-system when faced with smoke and fire; the vast expanses visible from the heights — are all evocative and moving. But the photo that I found the most stirring was the one of Ukrainian father displaying the flag of his home country. I hope our Congress sees fit to continue to support Ukraine’s struggle for survival soon.

I am pleased you made your ascent and descent without injury and that you were able to connect with both the natural world and with the people you encountered along the way. And that no one was polluting the landscape with golf balls. And thanks for checking on the etymology of Uncompahgre. I know Colorado is re-naming a number of its landmarks and trying to honour the people who were here first in the process.

LikeLike