Yearly, my job from mid-June to early July calls me to collaborate in wheat harvest with the farmers whose expertise and labor brings forth crops on my wife’s family’s land in southwestern Kansas.

This segment is the first in a series featuring mountains both real and figurative, climbs that are successful and not, and water that is varyingly life-giving, dirty, and toxic, as experienced by me and by those around me in July of 2023. All images, unless otherwise credited, are mine.

Life-giving water

The land and climate in this corner of Kansas are suited to hard winter wheat. We grow both the red and the white sub-types. Seeds are planted and sprout in September or October. Once established, the plants enter a dormant period for the coldest months of winter. On the other end of the hoped-for growth cycle, it is normal for more than 80% of the grain to be in the bin by Independence Day. The growing season in 2022-2023 was not normal, and soil conditions were adverse due to prolonged drought that had persisted from 2021 into spring of this year. The dearth of moisture at planting meant that the early growth of the wheat was hampered: it was too dry for vigorous sprouting and plant establishment. As a result, several fields produced no crop at all, because either the seeds never germinated or the initial stunted growth soon withered shortly after sprouting.

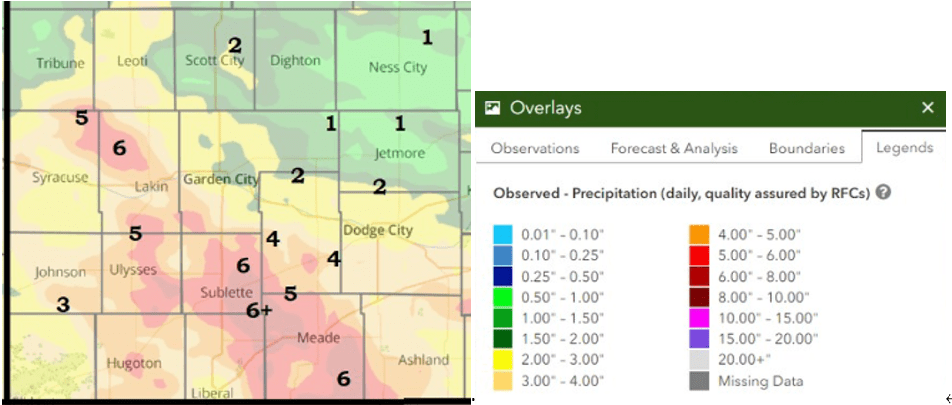

Elsewhere, the fields with plants that had come up and overwintered successfully did eventually see vital precipitation. In late April, rains came. And came. And came again. In those fields where the wheat was just hanging on, water gave the wheat back its life and its development resumed. Cumulatively, however, the poor start, combined with cooler than normal temperatures through much of April, May, and June, meant that the plants’ maturation period was prolonged well past the normal time for harvest. As a result, less than 10% of the surviving wheat was ripe and able to be cut as of July 1. (The best analogy that I can make is to a person sho suffered malnutrition from birth to age 25, whose hormones and behavior bring puberty in the 30s, functioning adulthood in the 50s, and parenthood in his or her 70s. How would that work with the other circumstances of a person’s life?)

Furthoremore, during the typically dryer period from mid-June onward, Ma Nature was still in the mood for rain (and hail!) and with a rebel yell she cried, “More, more, more!” Even when hail hasn’t knocked the berries to the ground, moisture this late degrades both the stalks and the maturing wheat berries, and it spurs weed growth which can cause grain loss when harvesting.

When rain comes, farmers know that it is a gift whose timing and size one can’t second guess. This is expecially true for a rain after drought. If a farmer’s head is tilted back, open-mouthed, to taste such a rain, it’s even odds whether the drops will carry the acidic sharpness of anxious waiting or the sweet notes of future fertility to his or her’s tongue. In some cases, one also tastes subtle the bitter edges of future futility. Rainwater can be heady stuff, and at the same time it can trigger an awful headache. While the late spring pile-on of water did give a hopeful start to life for the area’s spring-planted crops (e.g., corn and sorghum), it defeated the machinery with which the wheat is harvested. Consequently, between July 1 and July 7, we could only bring in another 10% of the crop.

By the 7th of July, enough rain had fallen to halt cutting for the foreseeable future, and I retreated from the muddy fields of Kansas to the mountains of Colorado. The wellbeing of family members needed tending, and I surely would be better for being with them rather than watching the waters recede. Look for more about them and my time in Colorado in the next post in this series.

If you enjoy what you’ve read, please post a comment. Likewise do so if you were troubled by it. Or use the contact button to send me a private message. And to have you subscribe to The PHurrowed Brow using the link below, well, I should like it of all things!

6 responses to “Water, Mountains, Climbs: I”

The value of so much in life depends on timing and proportion. Let’s hope hard for rain and snow in good time and reasonable measure and for everyone to work to mitigate the climate catastrophe that contributes to so many disasters.

LikeLike

By the way, how do the farmers deal with the uncertainty? How do they adapt and cope?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The answers to those questions are complex and situational. First. let me say that I haven’t asked the farmers’ permission to represent their expressed views. Consequently, I’d have to answer by reference to the somewhat true clichés about hope, faith, optimism, and a cautious commitment to accept innovations in crop selection, farming practices, and the like. But those *are* very important questions. Perhaps in 2024 I will shift the blog’s purpose from indulging in self-obsession to explanation of farming life as I come to understand aspects of it better.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You remind me of Victor Davis Hanson and his Other Greeks https://www.ucpress.edu/book/9780520209350/the-other-greeks. (Not to mention The Western Way of War, also based on his appreciation of yeoman farmers.) And the hard winter wheat you-all grow comes from Scythian (now disputedly Ukrainian) country via stalwart Mennonite immigrants from that area in the 1870s. Thanks for this emphasis.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you for adding the VDH title to my reading list, and for the well-informed link to historical context! I do hope that in future posts I can share more about the background of what we grow, where we grow it, and the tides of people who have shaped the landscape and communities of the region.

LikeLiked by 1 person

_The Other Greeks_ does sound like an apt supplement to this blog. Sounds as if you, Owen Cramer, and He of the PHurrowed Brow will be having some conversations that I am looking forward to reading.

LikeLike